I’ve wanted to start a blog for a long time. But somehow, I never got around to it. There were always things that seemed "more serious" and "more productive." Then, I realized how dangerous it is to take everything too seriously. And the moment I felt the urge to reflect on an important topic, I decided the time had come.

Today, I found myself thinking about the importance of loving well-made things—and why so many people lack this appreciation.

This thought came to me after I had a terrible experience using an app designed for remote doctor consultations (let's not call them by their name). In short: the inconvenient chat, the malfunctioning call feature, the confusing design — and I was increasingly baffled. How do people even launch a product that functions so horribly? The most well-developed feature of this service, of course, was the payment process. That part worked flawlessly. But the actual service was delivered so poorly and unpleasantly that it might as well have not been provided at all.

So what? There are plenty of low-quality things in the world. But they all share one common trait. Indifference.

What Is a Well-Made Thing?

I first encountered the philosophy of a "well-made thing" when I read an interview with Alain Passard. He talked about his career journey, what inspires him, why he transitioned from cooking meat to vegetables, and the art of aesthetically serving eggs (whole, on a stand, with an egg cutter). When asked what values are important to cultivate in children and in oneself, he listed several. One of them was "a love for well-made things."

But how do you define a well-made thing? What are its qualities, characteristics, and signs? "High quality." But what does that mean?

Dictionaries offer vague definitions like "high standards," "premium materials," and "above average."

I once watched a documentary about the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels—currently one of the most in-demand specialists in his field. His company wins tenders one after another. What’s interesting is that they win these tenders by offering low-cost construction. They use materials and processes in a way that makes their solutions the most affordable. Can we say their products are of poor quality just because they use inexpensive materials?

Bjarke’ sproject for Serpentine Pavilion 2016. https://big.dk/projects/telus-sky-4861

Conversely, what about luxury brands that offer expensive shoes made from premium materials—but they’re painful to wear? Can we call those high-quality products?

It all seems quite subjective. What’s "good quality" for one person might be "bad quality" for another. In my view, this subjectivity is precisely where the essence of a "well-made thing" lies—it’s something that evokes positive feelings in its target audience, a sense of satisfaction from solving a particular problem.

By that logic, Bjarke Ingels’ architectural solutions are well-made because they solve problems for two target audiences: developers, by enabling fast and efficient construction, and future homeowners, by prioritizing convenience, sustainability, and well-being.

The same applies to uncomfortable but beautifully designed luxury shoes. They are "good" because they fulfill the internal need of their target audience for an external display of financial status—or simply the pleasant feeling of belonging to the luxury category.

So, a well-made thing is one that satisfies its target audience.

Indifference in the Ancient and Modern World

They say people don’t change. And indifference is not a product of modern consumer society.

1. The Colossus of Rhodes

Estimated construction date: 294–282 BCE

What happened:

The citizens of Rhodes withstood the siege of Demetrius of Macedon (one of Alexander the Great’s successors). To celebrate their victory and resilience, they decided to build a statue of the sun god Helios (which, by the way, later inspired the design of the Statue of Liberty).

gravure sur bois de Sidney Barclay numérisée Google

They had no money. But they did have imagination. So they collected all the weapons left behind by the retreating enemy troops, sold them, and used the proceeds to fund the statue’s construction.

Then, the people of Rhodes became a textbook example of the "Why is it so expensive and taking so long? We’re not paying for this" type of client.

They commissioned Chares, a student of Lysippos (whose statue "Silenus with the Infant Dionysus" is displayed in the Louvre). Then things unfolded as follows:

Client (the citizens of Rhodes): We want the statue to be 18 meters tall.

Chares: Okay.

Client: Actually, let’s make it 36 meters

Chares: Sure, but I need to recalculate everything first.

Client: Here’s double payment, we’ll decide the rest later.

They never decided. The new height drastically affected the budget, and it turned out they didn’t have enough money after all. The project was already underway, and Chares continued working—funding it with his own and borrowed money. He labored for 12 years, but after finishing, he took his own life because he couldn’t repay his debts.

The sculpture collapsed 50 years later because it wasn’t heavy enough to withstand earthquakes. The money Chares borrowed was still not enough. Perhaps if the main client—the city—hadn’t neglected the project or had made a more reasonable decision from the start ("Let’s stick to 18 meters, but do it properly"), things would have turned out differently. And today, we might still be able to see one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

2. The Leaning Tower of Pisa

Foundation date: 1173

What happened:

This one is simple—the builders failed to account for the weak ground. The structure began to sink. Over the centuries, numerous attempts were made to reinforce and stabilize it. The last major restoration took place from 1990 to 2001. Engineers now believe the tower will remain stable for another 200 years.

.jpg)

https://coololdphotos.com/leaning-tower-of-pisa-in-the-1890s/

3. The Sydney Opera House

Why do most failed projects always seem to involve two recurring themes: "Let’s make it bigger" and "What does the creator know? Let’s replace him!"

Opening date: 1973

What happened:

Historically, Sydney residents had a growing need for cultural development. The government decided: "Let’s not just build a theater—let’s build a SUPER MEGA theater that will make everyone jealous! And of course, we will use taxpayer money for this."

https://www.sydney.com/destinations/sydney/sydney-city/sydney-harbour/sydney-opera-house

Taxpayers, however, frequently criticized the project for its high cost and inconvenient location (hard to access by public transport).

But why listen to your target audience? They don’t know what they want anyway.

The government held a design competition, which was won by Danish architect Jørn Utzon.

They got what they asked for—a challenging project: harsh environmental conditions, missed deadlines, unexpected problems, and expensive solutions. All seemingly normal for a serious architectural endeavor—a "new wonder of the world."

But not for Australia’s new government. In 1965, the new leader, Robert Askin, took active measures that seemed to say: "Why is this so expensive? And why are the deadlines being missed? This isn’t right—it must be the architect’s fault!"

Utzon was removed from the project, and he returned home.

The new team has started actively licking the government's ass optimizing processes. One of the key things they "optimized" was Utzon’s acoustic calculations—which were critical to the design. As a result, the sound was distorted. While this is rarely discussed publicly, musicians and conductors who have performed at the Opera House have repeatedly spoken about its flat sound and uneven distribution of acoustics.

The building has undergone multiple renovations to fix this problem. The most recent one was completed in 2022.

Utzon, by the way, refused to attend the opening ceremony. And he was absolutely right.

Can Indifference Be Overcome, or Are We Born with It?

I’m reminded of an interview with another chef. (I seem to have some inexplicable fascination with examples involving chefs). I don’t remember his name, but his story stuck with me.

He worked in a fine dining restaurant (speaking of high standards). He was used to a certain level of quality in food. And it drove him crazy that his wife could casually buy and eat something like a 7Days croissant.

.jpeg)

Soon enough, the problem solved itself. The couple went to Paris. After tasting the local croissants, the chef’s wife stopped eating low-quality sweets. "Better once a year in Paris, but done right, than every day and badly," she said.

To me, this suggests that a love for well-made things is a skill of sorts. A trained eye developed through active engagement. Immersion in a field. A small (or large) personal study undertaken for understanding and insight.

Someone unfamiliar with visual art might look at Malevich and say, "I could do that too." But if they spend a year studying the field (assuming they have a healthy curiosity and an open mind), they will eventually look at the painting again and think, "Ah, so that’s the point!".

Kazimir Malevich, 1915, Black Suprematic Square

Just like the chef’s wife conducted an empirical study to understand that a 7Days croissant is not an croissant at the Operá.

So, a love for well-made things is something learned — a skill. We either have someone help us develop it, or we cultivate it yourself.

Most public educational institutions lack a philosophy of humanism or the idea of "less, but better." And that’s why most people never develop this skill.

Why Some Manufacturers Don’t Care About Well-Made Things

Is "less but better" really preferable to "more but worse"? It seems so. Just think of the Colossus of Rhodes.

So why do 7Days croissants exist? Why does junk food exist at all? Why is there clothing that falls apart after a single wear, chicken fillets pumped full of water, apartment buildings with terrible insulation, and apps whose developers completely disregard usability in favor of dark patterns?

Leonard Cohen put it poetically and concisely in his song "Everybody Knows":

"Everybody’s talking to their pockets

Everybody wants a box of chocolates."

Is it really all just about profit?

The desire to make money is normal. Vincent van Gogh, despite struggling all his life, constantly thought about earning enough to avoid burdening his brother with expenses (beautifully described in Irving Stone’s Lust for Life).

-Vincent-van-Gogh-Met.jpg)

Wheat Field with Cypresses by Vincent van Gogh (1889). Metropolitan Museum of Art

The problem, in my opinion, is not that manufacturers want higher profits—it’s that they try to achieve this by lowering the quality of their products instead of adjusting their financial models.

This mindset has massive long-term consequences. By cutting corners now, a company stays in the game only until a competitor arrives—one with a more human-centered philosophy, who genuinely cares about their users.

The concept of profit, at its core, does not exclude a deep understanding of users and a commitment to making something of high quality.

In fact, quite the opposite.

With a love for well-made things and a drive for improvement and growth, creators build lasting trust with their users. And those users will stay.

Even when competitors come.

Even when the earthquakes hit.

What Happens When People Care

Stories like the Sydney Opera House debacle and similar cases (of which there are far more than I described) always leave me feeling frustrated.

So, I’d like to end this long read on a positive note. Here’s a list of things created by people who loved well-made things—things that continue to benefit us to this day.

1. The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome

Foundation date: 312 BCE (!) – 5th century CE

What happened:

The Romans designed and built an advanced water supply system. They used gravity to transport water over long distances, drawing it from clean mountain springs and directing it through channels with a slight incline. The water flowed naturally, without the need for pumps.

.jpg)

Aqueduct near Belgrade from Views in the Ottoman Dominions, in Europe, in Asia, and some of the Mediterranean islands (1810) illustrated by Luigi Mayer (1755-1803)

Every stage of the aqueduct project had to be approved by the administration, which operated under a fundamental principle: "Everyone has the right to clean water."

Of course, the system had its challenges—water contamination, maintenance difficulties in underground tunnels—but today, it stands as an inspiring example of a high-quality, human-centered approach.

Many aqueducts still function. For example, the Aqua Virgo, built in 19 BCE, is still used to supply water to Rome’s fountains.

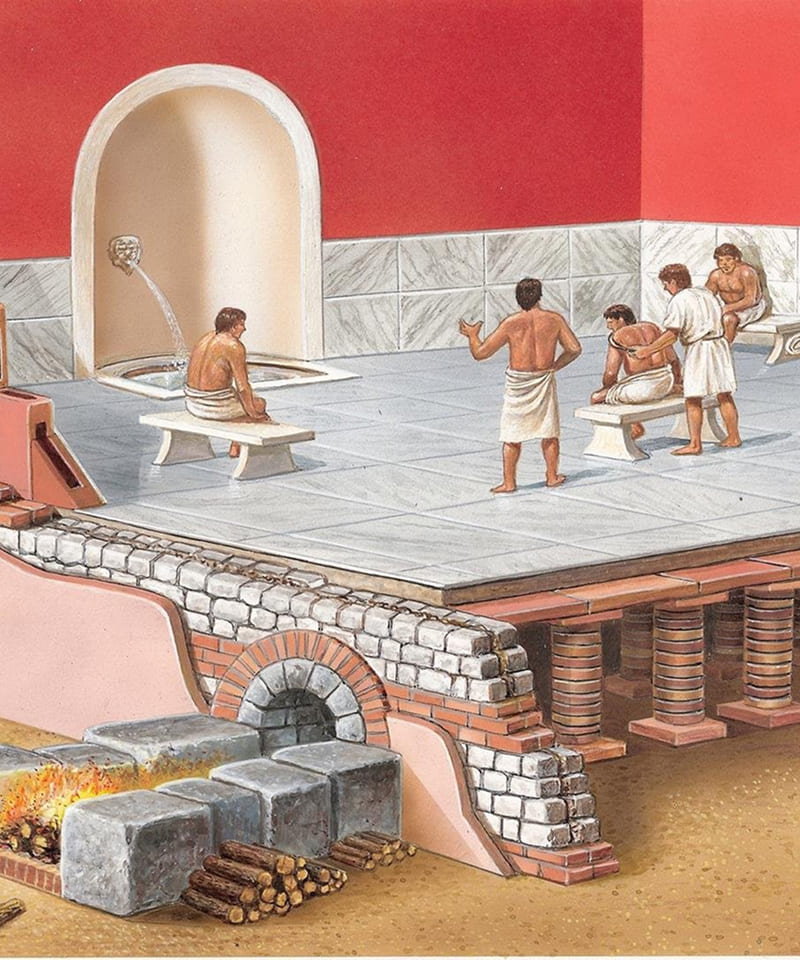

2. Underfloor Heating

Foundation date: 312 BCE (!) – 5th century CE

What happened:

The ancient Greeks developed a prototype of modern underfloor heating—the hypocaust—a furnace system with special channels and pipes that distributed warm air beneath the floor and into the walls.

The Romans later refined and expanded this system, making it a common feature in northern parts of the empire. Over time, the invention was forgotten, rediscovered, and improved by different civilizations—until it evolved into the heating systems we use today.

https://x.com/archeohistories/status/1897381172629684553/photo/1

3. The Espresso Machine

Foundation date: 1884

What happened:

The history of coffee is full of fascinating stories—from the Ottomans to a man named Georg Franz Kolschitzky, who is said to have opened Vienna’s first coffeehouse. There were French presses, cezves, and various brewing methods. But espresso machines owe their existence to the meticulousness and perfectionism of the Italians.

%20(1).gif)

As with many great inventions and theories (like Darwin’s theory of evolution), espresso machines were not the product of a single person’s genius but rather the result of years of work by many individuals.

Coffeehouses were booming, but there was a problem—it took too long to brew a single cup.

In 1884, an inventor from Turin named Angelo Moriondo patented the first steam-powered coffee machine. Aside from his blueprint, little is known about him. But his idea became the foundation for future innovations.

Two other developers took his concept and created a more advanced model. One of them, Luigi Bezzera, a liquor manufacturer with the resources to experiment, refined the machine to produce espresso in just a few seconds. However, he soon realized he had no idea how to market his invention.

That’s when Desiderio Pavoni entered the picture.

A talented entrepreneur, Pavoni bought Bezzera’s patent, improved the machine by adding a pressure release valve (preventing coffee from splattering onto baristas), and made other refinements. He promoted the machine at trade fairs and in advertisements, branding his new version as the Ideale.Almost poetry, isn’t it?)

Competitors followed, innovations kept coming, and over time, espresso and espresso machines evolved into what we know today.

When People Care, They Create Things That Last

There are countless other examples of things built by people who weren’t indifferent.

Yes, they wanted to be paid for their work. Yes, they sought recognition. But they never forgot the importance of research, refinement, and craftsmanship.

They never forgot what it means to truly love well-made things.

https://www.sydney.com/destinations/sydney/sydney-city/sydney-harbour/sydney-opera-house